Robert Arnott on yksi tunnetuimmista sijoitustutkijoista, jolla on usein myös kriittistä sanottavaa finanssialasta. Arnott oli vastikään puhujana Morningstarin etf-sijoittamisen konferenssissa Yhdysvalloissa. Tällä videolla hän kertoo pessimistisen näkemyksensä siitä, miten länsimaat - erityisesti Yhdysvallat -selviävät kolmen "d:n" dilemmasta. D:t ovat deficits (vajeet), demographics (demografia) sekä debt (velka). Arnott laskee Yhdysvalloilla olevan velkaa 37 vuoden verotulojen verran.

Ben Johnson: I'm Ben Johnson, director of passive funds research with Morningstar, on the sidelines of our ETF Invest 2013 Conference, and I am joined by Rob Arnott, chairman of Research Affiliates.

Rob and I are going to cover a number of topics today, starting with an update on the 3D hurricane five years later.

What do you see happening with these three key central issues that we're trying to work through?

Rob Arnott: The 3D hurricane relates to the interconnected influence of deficits, debt, and demography. And it's really just the flipside of what PIMCO refers to as "the new normal," a world of lower yields, lower returns, and slower growth, and those three headwinds interconnect and magnify the impact of one another.

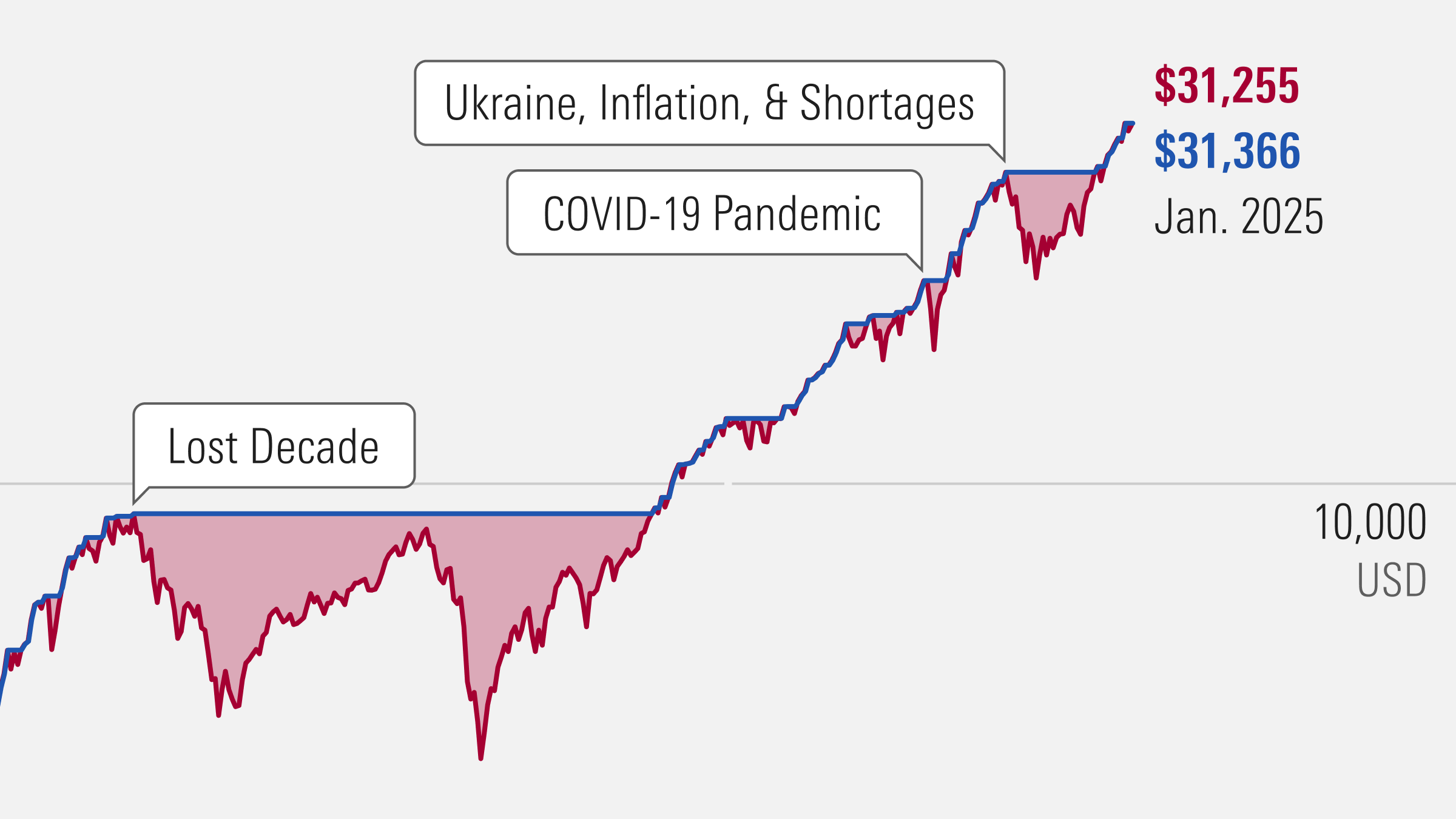

We're seeing Washington play out the first two pieces of that--deficits and debt--in a very big way this year. Notably, you're seeing really a battle for the soul of what this country is as a nation, and we've had deficits go through the roof. If you use generally accepted accounting principles, the deficits have been above 20% of GDP every single year since 2009. The debt crossed 100% of GDP a year-and-a-half ago, but under generally accepted accounting principles, it crossed 600% of GDP earlier this year. OK, these are big numbers. $100 trillion in debt in a country that takes in $2.7 trillion in tax revenues, so that's about 37 years' worth of taxes that we owe. That's a problem.

This runs headlong into demography, and the demography piece is subtle, but very powerful. We have a labor force that in the coming 20 years will be growing 0.5% a year. The last 40 years, it was growing 1.5% a year. That's a big difference. There goes 1% of GDP growth.

We also have a labor force that's older. Now, people reach peak productivity typically in their 50s. That means that their contribution to GDP is maxing out, not in their 20s or 30s, but in their 50s. People in their 20s and 30s are rapidly ratcheting up their productivity. They're wonderful for productivity growth. People in their 50s are great for GDP, but their growth in productivity is stalled, so their contribution to GDP growth is negligible. So, you've got an older labor force that's growing slower. Those combine to mean much slower GDP growth.

So, if we're accustomed to the notion that low yields mean lower returns, and that a slower-growing labor force that's older means slower GDP growth, if we embrace and accept that as a simple reality, a simple fact, we're going to be fine. If we fight it and say, "Oh, I refuse to believe it. I want to believe that the old normal is something we should aspire to return to," we can choose to embrace that pipe dream, but then we set ourselves up for our plans to be destroyed.

Johnson: So it sounds like we're set up for really what might be a very painful period of transition, or just trying to arrive at acceptance that what we've been through over the course of the past few decades has really been abnormal. So in PIMCO's view of the world, maybe the new normal is just normal.

Arnott: Well, it's not even quite that. I wrote a recent article in which my team and I showed that the old normal was abnormal and the new normal is also abnormal.

The last 60 years the developed world has had the most benign demography in the history of mankind. Support ratios associated with youngsters, supporting our children, was the lowest in history. Support ratios associated with senior citizens were still very benign, very light, because people hadn't gotten old yet. And now, we're in the wonderful circumstance of life expectancies being higher than ever before, and so we'll have more old people than ever before. That's wonderful, that's terrific, but it does mean support ratios going through the roof.

So, what we will transition from is an old abnormal of unusually benign support ratios to a new abnormal of unusually challenging support ratios in a transition to an eventual steady-state normal, where births equal deaths, and that's probably 50 to 75 years from now. So, we'll leave that to our kids and grandkids to worry about. But for now, we're looking at going from an abnormal where GDP growth was artificially inflated by about 1% to a new abnormal where it's artificially depressed by about 1%. It will feel like a 2% cliff, 2% slower GDP growth, horrors, except it's really just going from a percent above normal to a percent below normal.

And viewed in that context, if we're willing to accept simple facts, simple reality, we can say, oh, well, that's OK. Being prosperous with slow growth is fine, but the challenge is the expectations gap. There is nothing wrong with modest returns and slow growth. The thing that's devastating is expecting high growth and high returns, counting on them, and then having your plans dashed by that not materializing.

Johnson: And what do you think the effect will be of that? Will it be strictly psychological? How will people accustomed to a baseline 3% year-on-year GDP forecast reconcile these things?

Arnott: Well, firstly, why should they be accustomed to 3% year-on-year growth? The last 40 years, look at the statistics. For 40 years, real GDP growth in the U.S. has averaged 2.0%. 40-year GDP growth has averaged 2.0%, and yet we still anchor on 3% as normal. Oh my goodness. 40 years is a long time, and if 2% has been the average for 40 years, and we anchor on 3%, oh my goodness, what happens when it's 1%?

So, if we're in transition from 3% and an old abnormal with benign demography to 1% and a new abnormal with challenging demography, that transition in expectations is a real challenge. For most people, it's going to be pretty jarring. For people who simply look at the facts, low yield means lower returns; slower growing workforce means slower GDP growth. People who simply look at those facts and say, OK, I'll realign my expectations. What are they going to do? They're going to save more aggressively, spend more cautiously, work a handful of years longer, and they can be fine. Most people won't do that.

Johnson: How do you manage in such a world of low GDP growth, low returns? Does it just simply come back to saving, which as you've just said…

Arnott: …that's a big part of it …

Johnson: …that's a big leap of faith to assume people are going to save more.

Arnott: Well, it's a big leap of faith to assume people will save more. My advice to people is, save more. Now, whether they do it or not is up to them. When I mentioned at the start of the discussion that there is a battle for the soul of the country, part of that battle is those who didn't, who chose not to, saying, "Hmm, I want to have wealth reassigned from those who did save to me, because I didn't." They won't put it in those terms, but that's part of the populist agenda. And so, you do have this battle going on.

To be sure, there are likely to be some heartbreaking stories along the way, because people who have not prepared appropriately are living longer than ever before. Why on earth should we still retire at the same age as our great grandparents? If the average life expectancy across the developed world is now 80, and it used to be, when Social Security was created, life expectancy was not yet 65, and that was set as the retirement age. Does that mean that retirement age ought to now be reset to 80? I don't think so. But you could peg it at 90% of life expectancy and just index it. And if you did that, it would be 72. As life expectancy continues to go up, it drifts higher, and then you send a message, you're not entitled to live on the public nickel until you're 90% of life expectancy.

If changes like that are necessary, they will come. The political battles associated with getting from here to there are going to be monumental, but those transitions will come.

Johnson: And will be painful.

Arnott: They're going to be very painful for those who don't plan ahead.